Developers are becoming managers; managers are becoming developers¶

Now that software development tools like Claude Code and OpenAI Codex are agentic (i.e. LLMs using tools within a feedback loop to autonomously handle tasks), the traditional dichotomy of 'manager vs technical practitioner' is blurring. The mindset and soft skills of management are becoming directly relevant to technical practitioners. (And it only took ~1 year from a starting point of GitHub Copilot code completions).

Two things are happening simultaneously:

- Developers are increasingly orchestrating workflows rather than making every step-by-step decision.

- Managers and other non-technical knowledge workers are beginning to adopt and require understanding of agentic tools. (I envision a world where agentic tools are as prevalent as spreadsheets).

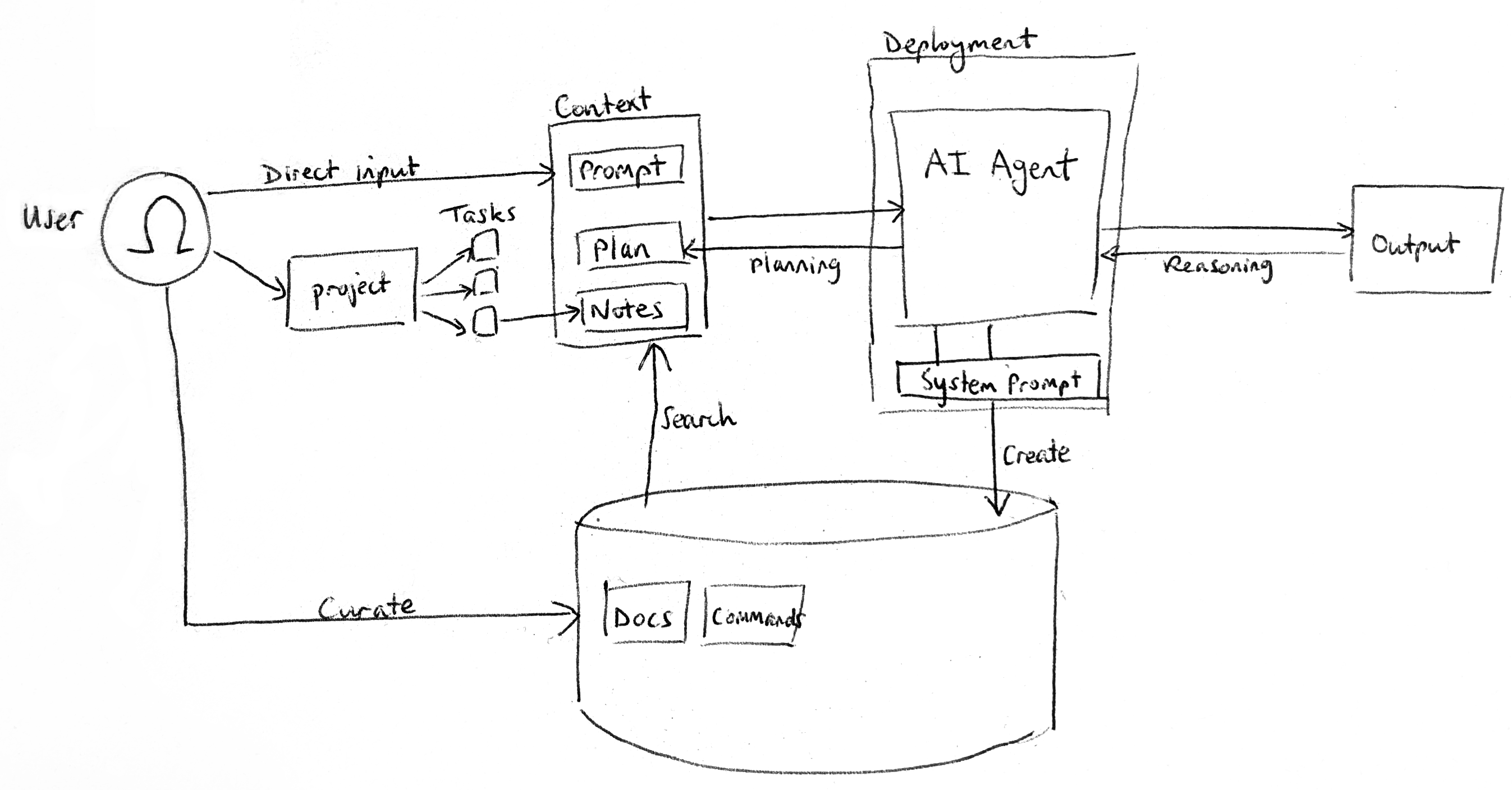

Context engineering is the next step beyond prompt engineering, and has emerged as the foundational playbook for 'how to use AI agents'. If prompt engineering is 'how to write instructions for LLMs', context engineering is a the broader discipline of ensuring an LLM has the instructions, tools and examples that it needs to complete its task(s).

- Anthropic's words: "Context engineering refers to the set of strategies for curating and maintaining the optimal set of tokens (information) during LLM inference, including all the other information that may land there outside of the prompts."

- Google's words: "The process of dynamically assembling and managing information within an LLM's context window to enable stateful, intelligent agents."

But, while context engineering is fundamentally a technology-first lens, viewed as an abstract system of inputs and outputs, agentic technology workflows resemble people management: success depends less on task-level execution and more on defining the context, boundaries and feedback mechanisms that enable workers to consistently produce quality outputs.

By bringing together these two domains, both developers and managers can find tactics to optimise how they operate.

Working with AI agents: define boundaries, context and feedback mechanisms¶

In this section, I'll lay out the main components of an AI agent workflow at a high level, focusing on Claude Code, and provide links to more detailed reference guides. I'm also aiming to cover the range of attitudes currently being displayed by the developer community towards this new technology.

Deploy & initialise with an appropriate blast radius¶

Initialising an AI agent looks something like this:

- Install Claude Code (straightforward).

- Define boundaries to limit Claude's blast radius (how many files could be hit if Claude decides to run a destructive command). By default it can access files in the directory where it is launched, and will ask for permission when running commands.

- To avoid "approval fatigue", consider running with

--dangerously-skip-permissions, ideally not in prod. - Consider running Claude Code in a Docker container with a mount to the source code (doing this isolates the underlying OS).

- Consider Anthropic's sandboxing feature.

- It's quite common (although not necessary) to utilise git worktrees to isolate files related to parallel tasks. Git worktrees allows checking out multiple branches into separate directories.

- Alternatively, you can give Claude it's own repo to play around in.

- To avoid "approval fatigue", consider running with

- Initialise Claude with

/init- it will create aCLAUDE.mdfile, which acts like a system prompt and should contain general principles for working on this repo/project.

Establish core, repeatable principles¶

We often want to give Claude guidance which applies across multiple tasks. CLAUDE.md is effectively a system prompt which gets automatically added into to any conversation with Claude Code, or in other words "the single most important file in your codebase for using Claude Code effectively".

There is no required format for the file; simply write a few useful commands and overarching principles (e.g. code style) that you want Claude to know about.

Here is Anthropic's example:

# Bash commands

- npm run build: Build the project

- npm run typecheck: Run the typechecker

# Code style

- Use ES modules (import/export) syntax, not CommonJS (require)

- Destructure imports when possible (eg. import { foo } from 'bar')

# Workflow

- Be sure to typecheck when you’re done making a series of code changes

- Prefer running single tests, and not the whole test suite, for performance

Depending on whether you want it to work at a repo, monorepo, subdirectory or system-wide level, place CLAUDE.md at an appropriate location.

Don't overengineer the CLAUDE.md file from the start of a project, just /init and add core principles like essential commands, style directives, building & testing workflows; and also make sure it has some project specifics like a summary of the project and repo structure. Then iterate over time as you work through the project (e.g. if Claude keeps making the same mistakes, make a note in this file).

Note that AGENTS.md is the non-Claude standard for this type of configuration file. You can effectively symlink a CLAUDE.md file to an AGENTS.md file by writing @AGENTS.md.

Manage the agent's context¶

An AGENTS.md file is used in every prompt; but you'll want to provide task-specific context to an agent (which takes us back to the concept of context engineering introduced above).

The main input from a user is obviously via direct prompting, which needs to be clear but otherwise is not particularly constrained.

Claude Code has a "custom slash commands" feature which effectively act as "shortcuts for frequently used prompts" or macros for common tasks (they can also work more programmatically, e.g. as templates which accept parameters/arguments, enabling more tightly scripted and advanced conversational processing).

For the purposes of context management, pre-built commands can be used to refine a simple linear conversational flow into a more effective branched one:

- Simply

/clearand start a new conversation. - Use

claude --resumeandclaude --continueto resume sessions. Session history is stored in~/.claude/projectsso previous conversation data can be analysed to look for common errors (e.g. to help refineCLAUDE.md). - Re-prompt often: hit double-esc, select a previous prompt and branch into a new conversation thread (somewhat loom-style).

- Alternatively use

/compactto summarise previous messages and continue a conversation - however in practice this is not as effective as branching/restarting. - Related: use

/contextto monitor your token usage.

In addition, you can simply ask Claude to read files or links (as per Anthropic: "providing either general pointers ('read the file that handles logging') or specific filenames ('read logging.py')"). Direct context provision in this way can handle images and diagrams (e.g. screenshots, design mockups, frontend results for iteration).

In fact, getting Claude to produce its own documentation is well-established pattern: before any non-trivial task, ask Claude to make a plan. Anthropic recommend using the word "think" to trigger extended thinking mode. You can also use more comprehensive 'brainstorming' prompts. AI agents are very good at reading code and can explain how to approach a large codebase in a "surgical" way. And if you're in pre-planning stage then you can also chat with Claude while doing research.

The outcome of a planning prompt should be a concrete written plan that guides Claude's implementation. More specifically, it should be a markdown/text file that gets saved in a logical place. It's a good idea to think about a "dev docs" system for managing these artifacts and any other notes that Claude takes, forming part of the knowledge base accessible to Claude. You can:

- add a /docs directory in your repo and tell it in AGENTS.md to save notes here (this applies to general notes, not just plans)

- extend this pattern of having a dedicated folder with associated guidance in AGENTS.md, with instructions like: "When exiting plan mode with an accepted plan, create task directory: mkdir -p ~/git/project/dev/active/[task-name]/ and note (a) [task-name]-plan.md - The accepted plan, (b) [task-name]-context.md - Key files, decisions, (c) [task-name]-tasks.md - Checklist of work. Mark tasks as done immediately after completing".

Once the knowledge base gets overwhelmingly large (e.g. 100s/1000s of separate note files) then it would become tricky for Claude to autonomously search them for pulling into its context. At this point, the retrieval system would need to be upgraded to RAG.

Give the agent access to tools¶

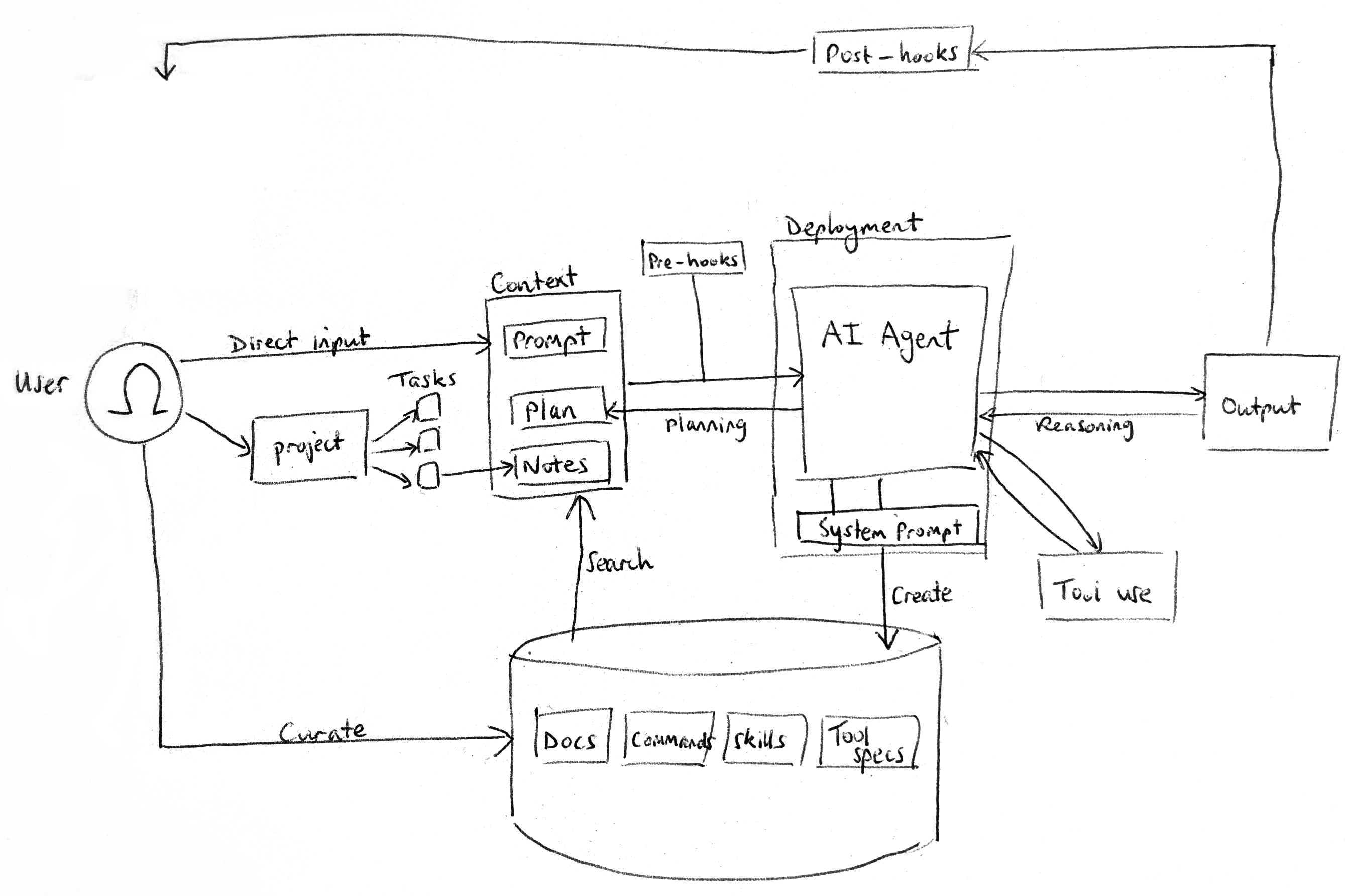

The ability to access a knowledge base is a particular example of the tool usage abstraction. The simplest way to think about tools is as additional functionality in the form of scripts/commands that Claude can autonomously decide to invoke when relevant. Claude already knows about common tools like unix tools and GitHub CLI from its training data, but becomes highly effective when extended with custom local tools (which should be listed in CLAUDE.md; MCP is generally not necessary)

Common tools to provide Claude include:

- file search: grep can be upgraded to ast-grep and/or ripgrep as and when Claude needs the enhancement

- semantic search: again, only add it when Claude might benefit from using semantic search to find more files to pull into its context. In practice, a blend of grep and semantic search works well.

- local custom scripts for establishing feedback loops - including test runners, log viewers and browser devtools/automation (e.g. to navigate and run JS to scrape webpages)

- bash enhancements e.g. token monitoring (overkill)

Similar to the concept of having a /docs folder that Claude can dump notes into, you can also maintain a tools folder like bin/claude that Claude can use as its first port-of-call for saving and retrieving ad hoc tools.

Sometimes it makes sense to add a bit of state to a tool (like resource files such as templates or utility scripts). In this case, Anthropic's abstraction is a "skill": "prompts and contextual resources that activate on demand [...] delivering specialized context on demand without permanent overhead". The setup is pretty simple:

- just a folder

~/.claude/skillsto contain skills which are basically just prompts, although should also include a bit of additional YAML frontmatter metadata - plus an overarching

SKILL.mdfile which lists skills. Best practice is "keeping the main SKILL.md file under 500 lines and using progressive disclosure with resource files"; however don't nest resources too deeply (Claude might use commands likeheadand miss some of the nested info), "keep references one level deep from SKILL.md".

It has become quite common to have a meta-skill which helps Claude to build new skills.

Sometimes Claude Code users find that skills don't always get triggered - this motivates adding hooks which can deterministically trigger on events like incoming prompts, output generation, or a tool being used. Some useful applications for hooks include:

- UserPromptSubmit hook (pre-generation): analyse an incoming prompt based on its intent/keywords, see if there is an associated skill that should be triggered, and inject a note like "REMEMBER TO ACTIVATE SKILL X" into the prompt

- StopEvent hook (post-generation): analyse the edits made by Claude and check for any risky patterns (e.g. if it added a sneaky placeholder), playing a custom alert to the user

- PostToolUse hook (mid-generation): save tool invocations into terminal history

Scale and manage the process¶

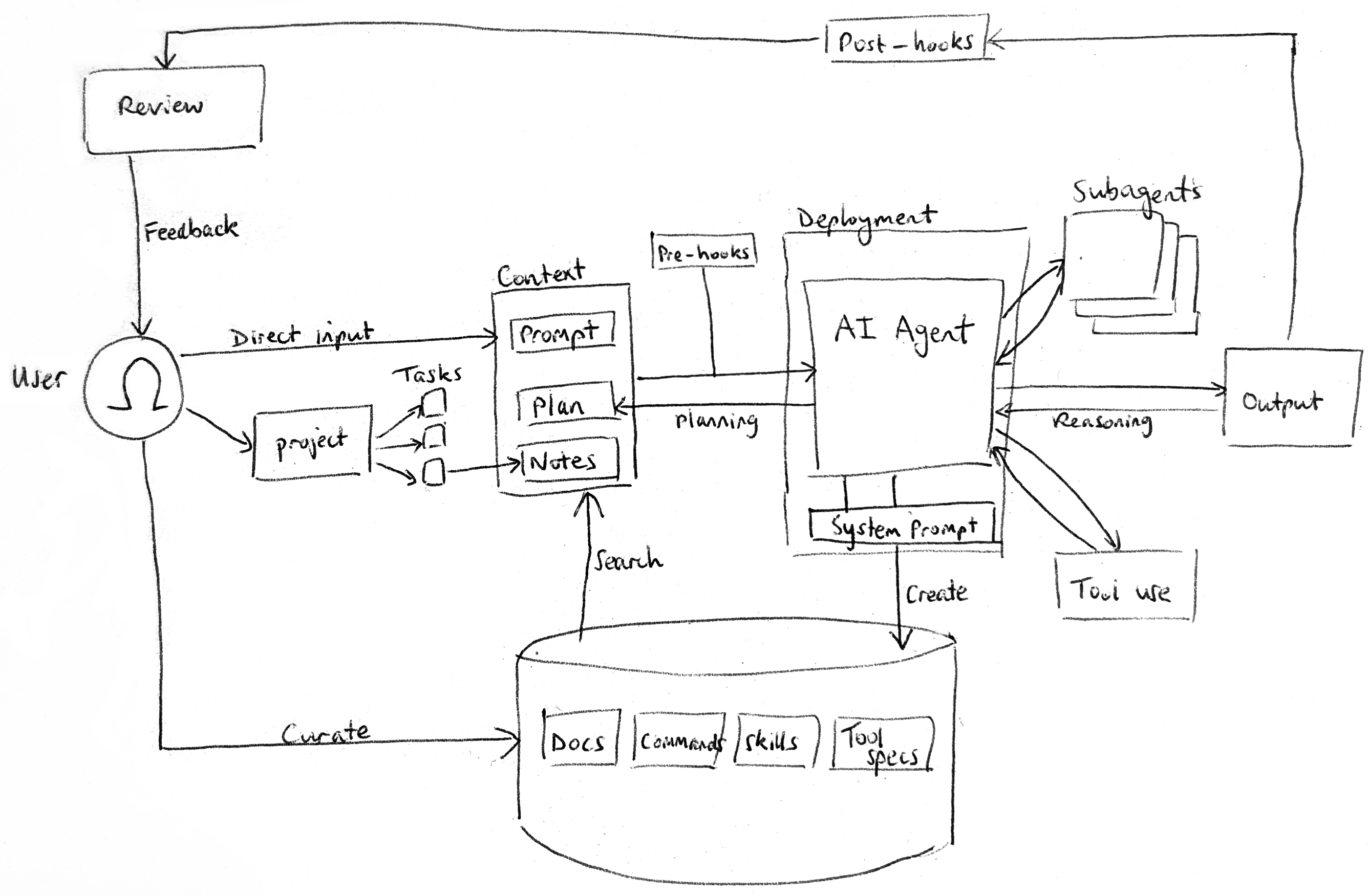

Now imagine that you want to encapsulate certain prompts, tools and skills into a single specialised entity that can be spun up and replicated on-demand. This motivates the concept of a subagent. Subagents can be triggered by the /subagents command or by adding @subagent into a prompt.

In their current state, subagents have limited capability, better suited to handling specific tasks rather than assuming full roles. As such, they operate best as a parallelisation rather than a collaborative multi-agent system.

This is essentially because subagents operate as ephemeral black boxes, handling subtasks (like one-off research jobs) but not sharing or persisting the details of their activity. This is good for avoiding pollution of the parent agent's context window, but means there is limited ability to work across multiple tasks even if those tasks have commonalities. They should be instructed to save intermediate results into a knowledge base, if the parent agent is expected to consume those results later.

Scaling subagent usage necessitates a robust test suite, even if simply due to the greater volume and breadth of changes being implemented. As edit volume grows, consider making changes as PRs and doing a first-line review with another AI agent (e.g. Claude or GitHub Copilot).

Think about future enhancements¶

The above points provide a reference of the current main components of an agentic coding system, but this will not be the end state of the tooling landscape. Future evolutions which we are likely to see include:

- more fine-grained control over model selection, to balance cost, performance and speed on different tasks

- subagents able to take on concrete roles in a 'team' abstraction

- more feedback loops between agents who can review, critique and improve each other

- greater emphasis on the front-end e.g. visual understanding and review of design, especially for browser testing (as in the new Google Antigravity)

- more headless automation, using Claude Code programmatically within CI/CD pipelines, at a higher-level of project abstraction, or to respond to failures

Managing teams and people: how does this relate to working with agents?¶

We've discussed the main features of agentic coding tools, which gives us a map of technologies for working with agents. The question now becomes: where are there overlaps between agentic tools and management principles?

For EMs, future teams might have a blend of human workers and AI agents; while developers have to 'manage' their tools ("treating it like a junior developer they need to manage"). EMs should think about their workflows as formalised systems that can be optimised; developers should develop managerial reflexes which aren't typically observed in technical IC culture.

As an engagement manager (EM), you are responsible for the project and your team. Your overarching objectives - which guide the managerial skillset and inform how agentic tools are likely to impact manager roles - are:

- Deliver high quality work for your stakeholders (e.g. clients)

- Develop the skills of your team

Understand and breakdown the project requirements¶

An EM spends a lot of time distributing work across their team. A project first needs to be clearly architected in terms of workstreams and timelines - packaging up the work to enable effective distribution and timely deliverables. The EM needs to function as the source of truth for scope and requirements, which might originally come from top-level stakeholders and a statement of work (SOW). For tech workers, a typical analogy is a Product Requirements Document (PRD). The EM needs to translate these requirements into a project plan which includes:

- requirements split into conceptual chunks (i.e. workstreams), to isolate the inputs for distinct deliverables and help the team understand which aspects are related;

- a high-level timeline, with focus on the non-negotiable milestones/deadlines.

With this, the EM can begin to think about driving progress forward. More specifically, they should think about:

- the processes (e.g. meeting formats/cadences) necessary for capturing and sharing knowledge across different parts of the project

- risks which might arise during delivery (e.g. dependencies between deliverables)

- the skills required to execute parts of the project to a high standard (e.g. what tools do the workers need to access? which individuals/models are best placed to help?)

Seconds describes a coding UX called "the captain's chair": "a single, long-running chat with a project management-type agent who dispatches subagents. The prime agent that you interact withs entire goal is only to manage subagents who do all of the coding and validation and task execution. Its job is to help validate the subagent behavior, stay on course, and on scope." In other words, coding UX is beginning to correspond to the EM’s role: a layer that translates requirements into structured work and keeps a constellation of workers aligned. The managerial instincts that make this possible in human teams are exactly the instincts developers will need when orchestrating agents.

Distribute work across the team¶

With foundations established, responsibilities can be delegated across the team. Mirroring how we currently prompt LLMs, the simplest form of delegation is direct task specification ("please do X"). It sounds obvious, but this prompt (to both humans and LLMs) needs to be clear - and this is not always straightforward to achieve. It can feel uncomfortable to delegate at first, but it's necessary; people want to be given a clear target that they can aim at. A task brief needs to contain a clear definition of success with enough additional guidance on "what good looks like" in terms of the EM's expectations of quality. This can mean specifying a format or style. These management principles have clear parallels when working with AI, like few-shot prompting and encoding a description of 'quality' in the AGENTS.md file.

A task brief should also capture a sense of the resource limits available to the worker. In a human context, this means almost always setting a deadline (including intermediate deadlines for reviews). It can be easy to forget to provide a deadline, especially if the project already has established milestone points, but time is a finite resource and the EM is responsible for making sure it doesn't get used up. In an analogous way, an agent, while not necessarily needing to be provided a time limit, can be told to avoid making changes to certain files to in some sense constrain its resources.

Evolving beyond simple task delegation, an EM is more effective if they can develop a bidirectional flow where their team members are proactively volunteering for tasks, taking responsibility for driving forward (parts of) the project to completion. Instilling a sense of ownership and empowerment in the team also leads to creativity (and higher quality of outputs) and more resilient, flexible processes. One test an EM should consider: have they become a bottleneck (if they were not available for a period of time, would the work stall)?

Agentic tools do not currently focus on facilitating proactive work suggestion; they still fundamentally wait for their human user to prompt with a new incoming requirement. Hierarchical waterfall, agent-as-orchestrator or swarm architectures might be future directions for multi-agent systems which operate more proactively. Currently, the simplest approach is to prompt "when you're done, suggest what we should work on next".

It's worth noting that, on occasion, team members can over-index on proactivity (for example if they want to impress a boss or client) and overcomplicate their work. By thinking about AI agents, we can find some tactics for dealing with this. The shortcut mental model which I often use when explaining generative AI to clients is that of the "enthusiastic intern" which needs managing; it will (generally speaking) always attempt its task but its outputs will need reviewing. The thought which this should spark for a managerial prompter is "how can we leverage enthusiasm to accelerate a project and enhance quality?". For example, we can ask an AI to always produce multiple versions of output ("please give me 5 ideas for X"). But we can also ask the enthusiastic worker, human in this case, to take on an additional task: namely, reflecting and improving upon its current work. Put simply, encourage the eager team member to put on a different hat (or apply a standard heuristic like finding the 'so what') and they can hopefully spot a more pragmatic approach. Sometimes the EM can pose a direct question to unpack this thinking: "your idea is X - how exactly would you do that?".

Naturally, humans are not always as likely as RLHF-trained LLMs to change their opinion to align with their manager's. For this, an EM tactic is, in appropriate situations where the downsides for the project and team are acceptable, to let them 'fail'. If a team member insists on their approach, then sometimes they only learn from experiencing its flaws first-hand. 'Gotchas' like these can be captured as learning experiences (e.g. to add to AGENTS.md); an example might be a junior who insists on designing an options analysis with lots of different columns, without realising that this creates a massive m*n spreadsheet of scores to populate.

Keep the project moving forwards by enabling your team¶

We previously saw how, when working with agentic tools, a planning stage can help an LLM to "decompose" a task into a plan, sometimes with questions back to the user, to improve its performance. The same process should be applied by an EM looking to move beyond prescriptive task delegation, thinking more generally about how to empower their team.

Some considerations for an EM engaging in a back-and-forth task decomposition with their team include:

- the EM should be flexible in how they define or frame a problem statement (for example, framing it like "as a customer, I need to be able to see X"), so that their team can fully understand how to approach it.

- team members should be encouraged to ask clarifying questions in a safe environment where "there are no stupid questions".

- the EM should be prepared to step in with experienced guidance, and when required make a decisive selection from multiple options. But they should also be open to recognising when they are being led by personal preference rather than what is best for the project (e.g. if a team member comes up with a more practical idea which is 'good enough').

- EMs are naturally inclined to lead these discussions with their juniors, but should cultivate the habit of leaving deliberate silence, especially if they have just posed a question for consideration. This space allows the team to think. Ibrahim Diallo puts it well: "Make room for some productive discussion. [...] frame the decision in terms of trade-offs, timeline, and user impact."

- to confirm that team members have understood the task, ask questions and get them to reiterate their understanding.

These considerations turn planning sessions into collaborative problem-solving exercises. Taking a metacognitive approach and understanding these exchanges as agentic input-process-output systems can help EMs to equip their team with the right context, knowledge and tools to do their work effectively.

There is a 'goldilocks zone' of context - providing too much context leads to worse performance as LLMs exhibit context rot and human workers get overwhelmed. The same principles applies to task lists and not just context: an EM should avoid trying to solve everything at once and should instead ruthlessly de-prioritise tasks which are not on the critical path to delivery. To make sure that relevant context is available when needed, a well-run project team naturally develops and curates artifacts such as meeting notes and design documents, but these only help if they are digestible and useful.

The EM must also be explicit about what context is missing. Seconds notes the importance of telling models the current date and their knowledge cutoff so they understand their own blind spots. Human teams benefit from this same transparency. Managers routinely overestimate shared awareness, assuming others hold the same mental state of the project. By contrast, stating uncertainties up front ("We don’t have updated data for X so assume Y") gives the team a more honest starting point. Clarity about ignorance is a leadership asset.

An EM who says "I'm not sure - let's figure it out" creates psychological safety and signals that uncertainty is normal, increasing the likelihood that team members volunteer suggestions (including with AI agents who become more likely to surface alternatives rather than making overconfident guesses or false assumptions). Transparent thought processes also create pedagogical experiences that can be formalised as concrete assets for future problem-solving by the team. As a consultant, I am trained to apply relevant frameworks to structure my thinking and solve problems in robust and understandable ways. Scaffolding an analytical approach not only helps human team members to understand and pick up (components of) a methodology, but can also enhance LLM performance (plus it's usually more efficient to solve something with the team rather than trying to carve out time for solo deep work). In simple terms, through demonstration equip your workers to apply techniques like "5 Why's" or "Root Cause Analysis" to add clarity and accuracy to their analysis. (I'm yet to try a claude/frameworks folder but think it would be interesting to equip an agent with a bank of frameworks such as this one).

Developers, unlike people managers, more rarely need to externalise their reasoning. In a culture which optimises for clean, working code, when something breaks it gets fixed immediately as the first priority. But for emerging, agentic workflows, the debugging cycle and internal rationale behind subsequent edits are valuable training signal (which is likely to be acted upon in an increasingly autonomous way). Like EMs thinking aloud during mentoring, developers who capture their decision processes will give their agents valuable 'meta-context' about heuristics, preferences and how to evaluate trade-offs.

Much as analysis frameworks can be formalised as assets to accelerate subsequent tasks, effective managers are concretely responsible for clearing blockers out of the way so that their team can deliver. Developers are perhaps more familiar with this process - more inclined to build scripts and automation tools to speed-up their work, and that of their AI agents. EMs need to cultivate the same reflex: if their team is getting stuck, or if there is a repeatable task, then the EM should look for ways to accelerate them. One potential trigger for this thought process is when a team is consistently pushing back; here a manager should take a clinical look to diagnose the friction and reconsider their approach if necessary.

Run effective feedback loops¶

Delegation is strongest when it is framed in terms of outcomes rather than tasks. It is unsustainable for an EM to direct a team on exactly what needs to be done (e.g. specific analysis steps, specific slides in a presentation) and more effective to allocate responsibility for achieving a certain outcome ("the client needs to understand why their revenue has declined", "we need to educate the client on the basics of AI"). But for an EM to stay focused on the 'requirements layer', they need to trust that their team can successfully translate outcomes into implementations.

Typically, this means providing regular and informative reviews (which could be as light-touch as responding to messages and leaving comments). More abstractly, the team member needs to have access to a reliable 'reward signal' which verifies whether their task is completed successfully, while helping them to develop their skills for the long-term. Another way that an EM can improve the fidelity of this 'signal' is by making their rationale clear: for example I like to explicitly say when I am making a professional recommendation as a senior on the team vs. when I am just making a suggestion for the team member to consider but potentially reject.

As such, feedback should be captured. I find it helpful to maintain a running note of feedback on each team member, so that in a performance review cycle I have a bank of real examples from which I can find trends. These should include positive examples: acknowledging genuinely good work (and not diluting this by 'sugar-coating' or over-acknowledging the bare minimum) is also a useful signal for reinforcing desired behaviours. The agentic analogy here is obvious: capture decision logs, review notes, diffs, etc., and codify trends back into AGENTS.md.

Just as robust feedback loops help humans verify whether they are on track, teams increasingly need analogous verification processes to manage the nascent capabilities of AI subagents. As we saw earlier, today's subagents are still relatively narrow in capability. Their competence determines the level of responsibility you can safely delegate: basic models can handle task-level work, while more advanced agents might be given role- or workstream-level ownership. Either way, the burden sits with the manager to ensure that parallelised work does not drift or conflict. In software terms, the same principle of frequent testing and QA applies. Similarly, a larger, layered human team should maintain alignment through regular check-ins, shared standards, and a clear definition of "done".

In an AI context, 'Best of N' is a standard generative practice for making high quality outputs. LLMs can generate several candidate outputs to evaluate and synthesise a superior answer. While human workers can't run themselves N times, we can emulate the underlying cognitive pattern of divergent and convergent thinking: explore multiple angles, sketch out prototypes, gather alternative perspectives by consulting a network of experts; and then converge on a decision. Peer- or self-review present ways to facilitate the convergence, and as Seconds states: "a powerful optimization tool is simply asking models to constructively critique or review their outputs".

Feedback does not only flow top-down or across peers. An effective leader seeks and accepts feedback on themselves. Team members should feel able to influence the processes in which they are operating. An agentic tools user might consider asking their LLMs for feedback on the user's own communication style.

Cultivate the environment¶

An EM is juggling multiple layers of responsibility and regularly context switching, operating in a role which is divided between clarifying and executing strategic intent. Fundamentally, their job is to make sure things get done. It's crucial that they are aware of their available levers - how can they adapt or escalate if things start to deviate from the plan?

When they join a new project or onboard a new team, they should already have a strong understanding of their ways of working (ideally codified as project planning templates and written principles). EMs can learn from the reproducibility instincts of software engineers to efficiently move into new projects: "Any power user of LLMs knows the pain and annoyance of setting up a new repo to try and get the agent to behave the way it does on one of your experience repos". The abstraction to consider here is that of the "harness" - the system which wraps around a coding LLM to track tasks, manage prompts and context, handle tool provisioning and enforce consistency. The burden on the user is to provide coherent direction, but the burden on the harness is to automatically augment and translate user intent into appropriate context to let the model succeed. As agentic tools become more mainstream, knowledge workers will find opportunities to leverage their past experiences to become more efficient and effective. EMs should ask themselves - what is the configuration that they want to capture and mirror across different projects and teams?

As agentic tools become more capable and more tightly woven into day-to-day work, the most effective EMs will recognise that the boundary between “managing people” and “working with software” becomes increasingly blurred and seek to understand formal strategies for relationship-management and metacognition. Their ability to structure projects, articulate requirements, cultivate psychological safety, give and receive feedback, resolve issues, and externalise their own reasoning will become directly relevant not only to human collaborators but also to the orchestration of AI agents.

Developers, meanwhile, face a cultural shift of their own. Once your tools have goals, memory, autonomy, specialisation and agency, you are coordinating entities whose behaviour must be directed, evaluated and coached. This is a fundamentally managerial approach, relying on the structuring of feedback loops, the skill of refining instructions, the habit of reflecting on one’s own reasoning, and the ability to build environments where team members can perform at their best.

The convergence is already underway. EMs who think like system designers will deliver more reliably; developers who think like managers will wield agents more effectively. Success will depend on leaders capable of navigating both domains with intention, clarity and an understanding that the tools we direct will increasingly reflect the ways we manage ourselves.